Tuesday, June 2, 2009

My Artistic Inerpretation of The Sea

Artistic Explication Through Song

Winkin', Blinkin' and Nod

Winkin' and Blinkin' and Nod one night

Sailed off on a wooden shoe

Sailed down a river of crystal light

Into a sea of dew

"Now where are you going and what do you wish?"

The old moon asked the three

"We've come to fish for the Herring fish

That swim in this beautiful sea

Nets of silver and gold have we"

Said Winkin` and Blinkin` and Nod

The old moon laughed and sang a song

As they rocked in their wooden shoe

And the wind that sped them all night long

Ruffled the waves of dew

While the little stars were the Herring fish

That lived in the beautiful sea

"Now cast your nets where ever you wish

Never afeared are we"

So sang the stars to the fishermen three

Winkin' and Blinkin' and Nod

So all night long their nets they threw

To the stars in the twinkling foam

Then down from the sky came the wooden shoe

Bringing the fishermen home

'Twas all so pretty a sight it seemed

As if it could not be

And some folks thought 'twas a dream they dreamed

Of sailing the beautiful sea

But I shall name you the fishermen three

Winkin' and Blinkin' and Nod

Now Winkin' and Blinkin' are two little eyes

And Nod is a weary head

And the wooden shoe that sailed the skies

Is a wee one's trundle bed

So shut your eyes while mummy sings

Of the beautiful sights that be

And you will see all the wonderful things

As you rock in your misty sea

Where the old moon rocked the fishermen three

Winkin' and Blinkin' and Nod

Just like the fishermen three,

Winkin', blinkin' and Nod.

That magical, mysterious quality of the sea that has been so prevalent in the other literature I've analyzed is the cornerstone of this lullaby. Described as “dew,” “crystal light,” “misty,” “beautiful” and “twinkling foam,” the sea is extravagant in the way a child would appreciate. I can still draw up the image of a wooden shoe, bobbing on a sea that sparkles like diamonds, cool and dark with a full moon with a jolly face talking to the fishermen. The song uses this imagery to create a calming but paradoxically effervescent effect. The foaming sea is full of herring fish, and the fishermen are excited to cast their nets and haul them in, but the focus is on the sea itself. The listener cannot escape the beauty of the sea that is so fantastical; no one believes it is real. Perhaps it is just a dream, but no child would ever mind if it were, because dreams and reality can be equally beautiful. This feeling of quasi-reality is brought on by the intoxicating sea. It is a feeling Edna describes in The Awakening when she first swims in the water, the night her conscience is awakened, and she admits to herself her feelings for Robert. Robert uses island lore—the legend of a spirit that awakens in the sea under the full moon on the 28th of July—to explain Edna’s bizarre feelings. Her recount of the night is of a dreamy quality, a feeling the fishermen share, describing it “as if it could not be.” Santiago, in The Old Man and the Sea, also finds himself caught between dream and reality on his seaward sojourn. Exhausted by the fish and nearly starved, he begins to become confused by who is doing the catching: the man? or the fish? Being alone in the open ocean is like wandering in the desert; there is nothing to get your bearings, no proof to nail you to the ground. Edna, Santiago and the fishermen all feel this weightlessness, the freedom and fear of being without an anchor. In The Sea Limits, the voice of the sea is called “desire and mystery.” This perfectly fits the relationship all parties have with the Sea, in their own individual way. Santiago and Edna have the same pull towards the water as any child, especially one who lives by the sea. The same curiosity and hunger for exploration drive all to the edge of the sea, some never to return again. As I have found, the Sea is a part of my life that I’m unwilling to let go. Moving forward, I cannot imagine myself striking up permanent residence away from the sea. Even when it simply an unseen presence, the familiarity and the comfort of knowing that the waves are still crashing is something I can’t be without. I know that like the three fishermen, I will always find a way back to the ocean, because it is a part of who I was and also who I have become.

Tuesday, May 26, 2009

Other Poems Concerning the Sea

Green, blue, gray and black

many moods it can have

happy and calme, mad and anxious

as the waves crash

stormy seas, stormy seas

turning the sky black

in its rage

in its fury

it makes boats crack

when it's sad

gray the water turns

making the clouds shed tears

it makes boats turn away

to head back to the piers

happy, blissful, joy and all

a nice sunny sky

compliments the clear blue water

the sea creatures rolling in the waves

as they foam white on

the surface.

La Balada del Aqua del Mar - Federic Gracia Lorca

El mar

sonrie a lo lejos.

Dientes de espuma,

labios de cielo.

¿Qué vendes, oh joven turbia

con lossenos al aire?

Vendo, señor, el agua

de los mares.

¿Que llevas, oh negro joven,

mezclado con tu sangre?

Llevo, señor, el agua

de los mares.

Esas lágrimas salobres

¿de donde vienen, madre?

Lloro, señor, el agua

de los mares.

Corazon, y esta amargura

seria, ¿de donde nace?

¡Amarga much el agua

de los mares!

El mar

sonrie a lo lejos.

Dientes de espuma,

labios de cielo.

(A loose translation)

The Ballad of the Sea's Water - Federico Garcia Lorca

The sea smiles at it in the distance.,

The teeth foam, at the edge of the sky.

What are you selling?

Oh yound cloud with the hear of air.

Sell, sir, the water of the seas.

What to bring, oh dark youth,

Mixed with your blood?

Carry, sir, the water of the seas.

These salty tears,

Where do they come from, mother?

Weep, sir, the water of the seas.

Heart, and this bitterness,

Truly, where is it born?

So much bitter water of the seas!

The sea smiles at it in the distance.

The teeth foam, at the edge of the sky.

Among the Rocks - Robert Browning

Oh, good gigantic smile o'the brown old earth.

This autumn morning! How he sets his bones

To bask i'the sun, and thrusts out knees and feet.

For the ripple to run over in its mirth;

Listening the while, where on the heap of stones

The white breast of the sea-lark twitters sweet.

That is the doctrine, simple, ancient, true;

Such is life's trial, as old earth smiles and knows.

If you loved only what were worth your love,

Love were clear gain, and wholly well for You:

Make the low nature better by your throes:

Give earth yourself, go up for gain above!

Annabel Lee - Edgar Allen Poe

It was many and many a year ago,

In a kingdom by the sea,

That a maiden there lived whom you may know

By the name of Annabel Lee,

And this maiden she lived with no other thought

Than to love and be loved by me.

I was a child and she was a child,

In this kingdom by the sea

But we loved with a love that was more than love-

I and my Annabel Lee,

With a love that the winged seraphs of heaven

Coveted her and me.

And this was the reason that, long ago,

In this kingdom by the sea,

A wind blew out of a cloud, chilling

My beautiful Annabel Lee;

So that her high-born kinsmen came

And bore her away from me,

To shut her up in a sepulchre

In this kingdom by the sea.

The angels, not half so happy in heaven,

Went envying her and me -

Yes! that was the reason (as all men know,

In this kingdom by the sea)

That the wind came out of the cloud one night,

Chilling and killing my Annabel Lee.

But our love it was stronger by far than the love

Of those who were older than we -

Of many far wiser than we -

And neither the angels in heaven above,

Nor the demons down under the sea,

Can ever dissever my soul from the soul

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

For the moon never beams without bringing me dreams

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

And the stars never rise but I feel the bright eyes

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

And so, all the night-tide, I lie down by the side

Of my darling -my darling -my life and my bride,

In the sepulchre there by the sea -

In her tomb by the sounding sea.

This is an excerpt from one of T.S. Eliot's quartets, Number 3:

The Dry Salvages - T.S. Eliot

The river is within us, the sea is all about us;

The sea is the land's edge also, the granite

Into which it reaches, the beaches where it tosses

Its hints of earlier and other creation:

The starfish, the horseshoe crab, the whale's backbone;

The pools where it offers to our curiosity

The more delicate algae and the sea anemone.

It tosses up our losses, the torn seine,

The shattered lobsterpot, the broken oar

And the gear of foreign dead men.

The sea has many voices,

Many gods and many voices.

Sunday, May 24, 2009

Conclusively: The Sea In Literature

In The Awakening, The Old Man and the Sea, and The Sea-Limits, it is evident that the Sea is a magnet for all kinds of people. The doubtful, the trapped, the willing, the passionate, the worldly, the listless--all find something unique to them in the sea. In The Awakening, the sea acts as Edna's conscience. She doesn't realize the correlation directly, but her freedoms give her liberty in the sea, and her darkest days are stormy. Eventually, the sea ends her conscience forever. What was born there must die there, so it makes sense that the awakening that she generated in that ocean would reclaim it. This is similar to the ocean in The Old Man and the Sea, where the sea gives Santiago the greatest fish of his life, and good weather, but reclaims the fish to feed its own creatures. This would make the sea appear selfish, but in reality, it is indeed a giving being. It gives when a human is in need, whether it needs encouragement or a Marlin. The sea simply has too many things to look over, however, and cannot give wantonly. It has to keep tabs on who has taken what, and must get them back. Keeping that under consideration, the sea does not treat Edna and Santiago equally. It upends Edna's life completely. It changes her, lets her see things she had never seen. It wakes her up and lets her see what life should be--but then takes away everything. For Santiago, the sea has always been a constant companion. It gives him fish and wearies his body and soul in return. But this fish is different. It is the greatest achievement he could have dreamed of, if he can only battle the pain. And he does. But the sea's loss is not equal to Santiago's, so she takes it back. In The Sea-Limits, the sea is not something man can associate with life, but rather life itself. As the marker of the passing of time, the sea is a super-being. It is beyond human understanding, and the only way we can see it is through that lens of the extraordinary. It is not just a companion but a guide, even a guardian.

The sea has long been an important part of literature. Its vastness and mystery are unmatched by any other aspect of nature. The sea cannot be contained, manipulated or moved without significant consequences. It's giving and kind, but ultimately just and fair, a protector of its creatures, and oblivious to petty human issues. How each individual approaches the sea is reciprocated. One's relationship with the sea is determined by one's own fears and expectations. Time has been kept as long as the sea has beaten upon the shore, and man has always sought to understand it, often only to find that what they were looking for was inside of themselves already.

just and fair, a protector of its creatures.

The Sea-Limits (Literary Work Three)

Consider the sea's listless chime:

Time's self it is, made audible-

The murmur of the earth's own shell.

Secret Continuance sublime

Is the sea's end: our sigh may pass

No furlong further. Since time was,

This sound hath told the lapse of time.

No quiet, which is death's -- it hath

The mournfulness of ancient life,

Enduring always at dull strife.

As the world's heart of rest and wrath,

Its painful pulse is in the sands.

Last utterly, the whole sky stands

Gray and not known, along its path.

Listen alone beside the sea,

Listen alone among the woods;

Those voices of twin solitudes

Shall have one sound alike to thee:

Hark where the murmers of thronged men,

Surge and sink back and surge again-

Still the one voice of wave and tree.

Gather a shell from the strewn beach

And listen at its lips: they sigh

The same desire and mystery,

The echo of the whole sea's speech.

And all mankind is thus at hear

Not any thing but what thou art:

And Earth, Sea, Man, are all in each.

In The Sea Limits by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the sea is abstract. It is a lens used to view the passing of time, and existence. Called the “murmur of the earth’s own shell”, it is seen that the sound of the sea—the pounding of waves perhaps, is time “made audible.” Such a divine idea, that the ocean has always told the passing of time, that there has been no time unmarked by the crash of a wave, must come from a speaker with time on his hands to philosophize, in the least. Also, most likely, someone who is thoughtful, romantic and listless. Tackling eternity is a journey that takes flexibility and comfort with the self.

The speaker is focused on the sound of the sea as a central figure, and relates everything back to it. He even recognizes that silence, or the lack of the sea, is death. As he states, when the “painful pulse” stops, the sound of the waves, and life, is lost. The sea is the sound of life, the way Christ is the rock of faith. You can’t have life without clinging to that sound, the way Christians must cling to their foundation. The speaker is using the sea, or rather the sound of it, as a foundation for life. The woods also have the same eternal sound, according to the speaker. The sea and the woods will have “one voice” of “twin solitude.” The speaker may want the reader to appreciate that despite the murmurs of the “thronged men” that “surge and sink back and surge again,” the voice of the woods and the sea remain. Or rather: despite humans that invade nature on land and in the sea, the sea and the earth will always remain, retaliate, if not simply survive the damage inflicted upon it by civilization. Nature is eternal, unceasing and as old as time, and no inconsiderate population of humans can destroy it, anymore than they can stop time from passing.

That being said, if man “listens at [the] lips” of nature, he can understand it, and understand the “same desire and mystery.” This is just to say that if mankind could respect nature, then “Earth, Sea, Man, [would be] all in each.” If we understand the sea, or nature in general, we can understand each other, and our connection to the greater world, even our place in the universe. This interpretation of life through the sea helps the reader grasp what the reader is trying to say about time, the way it is eternal and unfathomable, the way counting the breaking of waves is impossible. It is also important to know that mankind is not meant to do such things, and should remain at peace with the environment and make every wave count. We don’t have forever, after all. Someday we will all hear only silence.

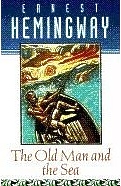

The Old Man and the Sea (Literary Work Two)

As Santiago catches his great fish (a leviathan, 18-foot Marlin), he embarks on a three day journey that drains him of all strength, and tests his resolve to the utmost degree. The sea remains his constant companion as the fish tows him further and further from home. His fishing expertise makes him so at home with the water, he can read things in it like a book. The weather, his location, the nearby fish, plankton and sea creatures--everything that is a part of the Sea is a part of the Old Man. He describes the turtles of the sea, and how so many people are heartless about them, because a turtle's heart will "beat for hours after he has been cut up and butchered' (37). But the Old man knows that his heart is just like theirs, and his hands and feet are just like theirs, and he, too, depends on the sea for life, and isn't so foolish as the other people. These small revelations of Santiago continually show his life-earned wisdom and patience, and the impressive respect he garners for all things, especially the Marlin he follows. He often calls the fish "brother", and wishes the fish as much luck in killing him as he has to kill it. The life or death struggle must be lost by one of them, and the Old Man would be honored to have it go either way.

The great respect for nature, epitomized by his respect for the sea, is Santiago's greatest strength and weakness, together. The sea gives him challenges and rewards in the Marlin, but also traps him. When Santiago finally catches the Marlin, he is still a long way from home, and the creature is too big to bring into his boat. As Santiago tries to bring it home, he is attacked, over and over, by sharks, the hungry scavengers of the sea. The Old Man is exhausted and upset. He knew it was "too good to be true" to catch the Marlin, but had hoped to bring some of it home. But like a woman, the sea takes back what it has given. The Old Man barely makes it back home alive, as the sea gives him a gift, a Trade Wind, to drift home alive. "The wind is our friend...the great sea with our friends and our enemies" (120). Santiago cannot control what the sea throws at him, friend or foe, but he can do his best with whatever it is.

The greatest lesson the Old Man learns from the sea is that of nature's intentions. If he was meant to have the fish, he would have the fish. If he were meant to find another, he would. He is humble, but proud of his fishing skills, and willing to take what la mar will offer him. He knows that "no man was ever alone on the sea" (61). The sea is used to show Santiago's trust in nature, his infinite patience and quiet wisdom. The sea is indeed his friend, but brings him hardship as well. Santiago could never live without the sea, because while it frustrates him, and dangles hope in front of him, it is all he knows, and it sustains him, because he was born to be a fisherman, and a "fisherman must fish".

Friday, May 22, 2009

The Awakening (Literary Work One)

Edna's journey is notable because it is not tragic or horrific, nor does it occur in extreme circumstances. She's just a discontent woman, who has previously been unable to admit her unhappiness. "Happily" married with three children, Edna should be enjoying her summer holiday. But when her husband returns home late one night, doting and over-attentive, the confused Edna is driven to lonely tears. She doesn't know why her discontent is making her so frustrated, but she hears the sea calling as a "mournful lullaby upon the night" (11). Edna's inexplicable depression is only slightly eased by the presence of Robert, the fun-loving, flirtatious twenty-something who spends all of his free time following Edna around the island. On their daily walks to the beach, a "soft and warm" breeze springs up (24) as they approach the sea. The clear alleviation of stress in Robert's presence is what leads Edna to her self discovery, when she slowly begins to "realize her position in the universe as a human being" (25). This was radical in Chopin's time, that a woman would think of herself as an individual, outside of her societal roles. The longer Edna entreats herself with Robert's presence, the more she finds the sea to be "seductive" and "sensual", its voice "never-ceasing, whispering, clamoring, murmuring" (26). As she embraces her womanhood and her connection with Robert, she sees herself, and also the sea, in a new way.

Edna's true revelation happens one night after a dinner party. As Edna recounts, until this point in the summer, she had been unable to swim. After lessons from nearly every person present, she still felt an "ungovernable dread" when she was in the water, always fearful unless she had the reassurance of "a hand nearby that might reach out and reassure her" (52). If we attribute this to Edna's mental state, we can know that Edna has always been afraid of being alone, and of the truth. She hasn't wanted to know the unknown, she hasn't had the desire to venture out alone. Her fear in the water was debilitating, but since she had her husband and children, and her seemingly perfect life, she didn't need swimming-- she didn't need knowledge. After her experience with Robert and in the process of finding herself, Edna wants to cast of her ignorance, her innocence, and find a way to swim. She does, and the feeling she gets is of "exultation." She wants to swim where "no woman had swum before" (53), to completely let go. Little does Edna know that that is exactly the path she is embarking upon, taking up a mantle that few women of the time had the courage to take, to make decisions based on her own desires and no others. But at this time, Edna is not prepared to leave the life she knows completely. Looking back to the shore, she feels the dreaded fear, and it "appall[s] and enfeeble[s] her senses" (54). On this evening of epiphany, Edna makes her first act of truly free will.

As Edna revels in her new-found freedom, she notes that the air is "pregnant with the first-felt throbbings of desire" (57). Until now, Robert's presence was comforting and liberating, but with her new ideals, she allows herself to see Robert in the light he has always been standing in. She begins to truly love Robert here, although she doesn't admit it until much later. Also for the first time that night, she openly defies her husband's wishes. She refuses to go to bed simply because he wants her to. She stays on the porch all night, and he, dumbfounded, accompanies her in silence and confusion. Edna's journey truly begins her. Her liberation in the sea signifies her liberation of consciousness. She begins a year of protest, self-fulfillment and discovery. She stops hosting her husbands visitors on tuesdays, because she doesn't want to. She starts visiting friends from the island, painting to make a living, and going to the races. Mr. Pontellier goes away, and the children go on holiday as well. In this time, Edna entertains male callers, buys a small house of her own, and secretly yearns for Robert. She cuts off all of her old loyalties to her husband, who follows her tracks, covering them to make sure the family appearance is upheld, never, however, suspecting adultery. Curiously, when Edna does succumb to her natural desires, she feels the guilt of betrayal, not to her husband, but to Robert, who has run off to Mexico.

Edna's freedoms hold throughout the year, until one day, Robert returns to town. She is almost wild in her desire to see him, but fearful of his response. When they finally make their vows of undying love for one another, Edna's free spirit seems unquenchable, and she is prepared to find a way to get out of her marriage and be with Robert. She explains that if Mr. Pontellier thought he had some sort of claim on her, she would laugh at him. This is, assumably, somewhat confusing to Robert, since women of the time were in marriage for life. Their love dies as quickly as it flourishes, since Robert disappears, leaving the note "I love you. Good by--because i love you." (215). Robert was unable to accept Edna's freedom the way she had. Edna's heartbreak is devastating, and she returns to the island for a final swim. She still describes the sea as seductive, never-ceasing, whispering, clamoring, murmuring, etc. She casts of her clothing, standing naked in the open air, "like some new-born creature, opening its eyes in a familiar world that it had never known" (220). The foam she describes as "serpents", the water as "chill", but, she reminds herself, sensuous. She feels it has "no beginning and no end" (221). She swims on and on, pushing her conscience off of herself until she is left with nothing. Her despair is unending, like the waves of the sea. She fittingly ends her life in the sea which had given her life in the first place. The sea is Edna's beginning and end, her joy and misery, her self and her environment.

Friday, May 15, 2009

The Sea

So if the sea is so powerful, where does that leave us? Are we just mindless creatures drawn to the pounding waves, the way insects are drawn to shining lights? It's so inviting, we ignore the danger. We can't help ourselves. But when we get there, things aren't so simple, because we aren't mindless. The sea draws different people for different reasons. Some seek confrontation, others seek healing, but we all somehow find a way to see what we want in that great expanse of water.

But perhaps it would be more astute to investigate what the sea wants with us. If we considered the sea as a character, or even just as a foil, used to show us what we should find in ourselves, we might begin to understand it. This is what I will investigate through several literary works. My mission is to discover how authors use the sea to help characters understand themselves, and for readers to understand the characters. And perhaps, along the way, I'll learn more about what the sea means for me as well.